The origin of the “transient” skin microbe concept

Published:

There is a growing appreciation that microbes are not all pathogens. Some of them are important to our health, and many of them seem simply irrelevant to our concerns. It was only a matter of time before Purell put the following question and answer on their webpage’s FAQ:

Does PURELL Instant Hand Sanitizer kill the good germs and the bad germs?

Germs live all around us. Our bodies are covered with germs that help us stay healthy. These are considered “good” germs and, since they reside on the body, are referred to as resident germs. In addition to the good germs, we are also exposed to ones that we pick up from contact with other people or objects. These are called transient germs. It is these germs that are often responsible for making you sick. Similar to washing your hands with soap and water, PURELL products reduce some of your resident germs while killing the transient germs. However, in both cases, your body quickly regenerates your resident germs which are generally harmless and actually important for healthy skin.

You might think that Purell is spouting its own party line, making up this convenient distinction between resident, “good” microbes that replenish themselves after a perturbation and the transient, “bad” microbes that are only loosely attached. As Kong and Segre, two leading skin microbiome scientists, note in a review, this attitude toward residents and transients is specific to the skin. They say, “Our current society paradoxically strives to colonize our guts with probiotic yogurts, but sterilize our skin with hand sanitizers.”

In that same review, however, these two scientists do describe the resident/transient division as one of the basic organizing concepts of the skin microbiome:

The microbiota is generally conceived of as two groups. (1) Resident microbes belong to a relatively fixed group of microorganisms that are routinely found in the skin and that reestablish themselves after perturbation. Resident microbes are often considered to be commensal, meaning that the microbes are not harmful and may provide benefit to the host. (2) Transient microbes do not establish themselves permanently on the surface, but rather arise from the environment and persist for hours to days. Resident and transient microbes are not pathogenic under normal conditions if proper hygiene is maintained and if the normal resident flora, immune responses, and skin barrier function are intact. However, after perturbation, resident and/or transient bacterial populations can colonize, proliferate, and cause disease.

During my PhD, I became curious about the experimental support for this idea. I found that many of the recent reviews and papers cite one another until, eventually, they cite a textbook (Marples’s 1965 Ecology of the Human Skin). Marples in turn cites a 1938 paper as justification for the resident/transient division.

Philip Price, the author of that paper, begins by saying that although a “huge amount of work” has been done investigating the “bacteriology of normal skin” (what we would call the “skin microbiome”), “present day knowledge of the subject remains fragmented and uncertain”. Price decides, in part, to unify previous observations about the quantity and location of skin microbes through a novel experiment:

The underlying principle of the test is simple. If hands are washed in a basin of sterile water, a large number of bacteria will be removed. By plating and culturing measured specimens of the water, counting the colonies, and multiplying by total volume, the exact number of bacteria removed can be calculated. Now if we use a long series of basins, scrubbing the hands and arms in each one in turn for the same length of time in a perfectly uniform manner, the washings will be found to contain progressively decreasing numbers of bacteria. Cumulative totals of organisms in these basins, therefore, when plotted against time, form a curve. Furthermore, it has been found that this is a regular, logarithmic curve which can be projected mathematically to zero. Hence it is possible to place the curve accurately in relation to the base line and to determine its real value.

In other words, Price washed his hands in one washbasin for 1 minute, then in another basin for 1 minute, then in another, and so forth. Foe each basin, he took the wash water, poured it over a Petri dish, and counted the colonies that grew. If you assume that zero bacteria will be left on your hands after washing for a long time, and you assume the number of bacteria on your hands falls exponentially with time, then you can fit those “lost microbe” counts to this model.

The results are so quaint:

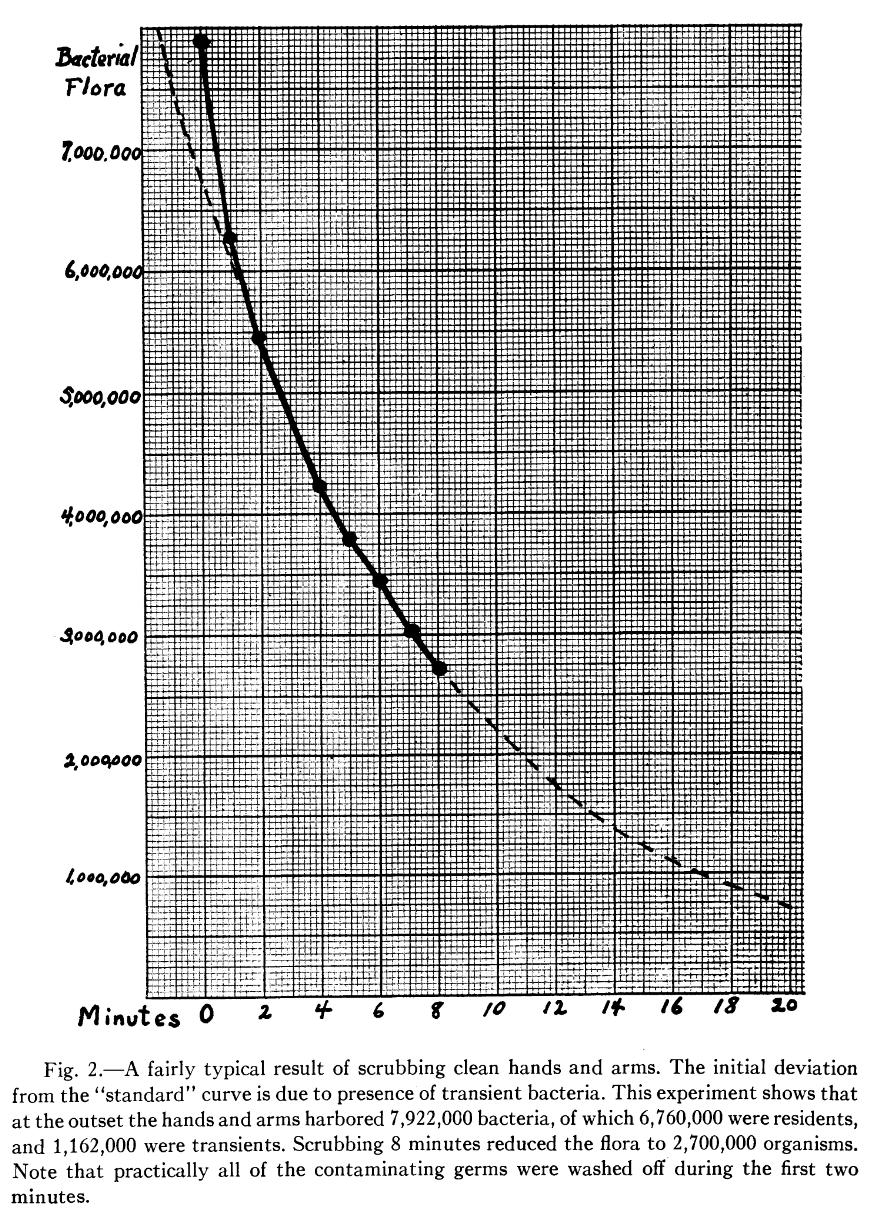

Table 1 and figure 1 show the results of one such experiment. It will be seen that in this instance the hands and arms at the beginning of the experiment were found to harbor a total flora of 4,580,000 bacteria, that scrubbing reduced this flora at a constantly diminishing rate, and that at the end of 14 minutes of washing, 1,000,000 germs remained on the skin.

He performed this experiment 80 times over the course of many years and found that the pattern and fit parameters remained similar.

The major support for the transient concept, even as cited into our own literature today, hinges on this experiment result: the first timepoint always lies above the line. In other words, more bacteria than expected fall off the hands during the first minute of washing. Price concluded that there are two sets of mechanics going on: transients are loosely attached, and they make up this “extra” lost microbe count in the first timepoint. The residents are more deeply rooted, and they are removed according to the exponential law.

On the one hand, this is an excellent and truly elegant experiment. It definitely shows that there is something going on in those first few minutes. I’m only disappointed that this experiment hasn’t been repeated in some modern setting where we could better figure out who those different microbes are.

Is it true that the majority of those easily-detached organisms are pathogens? Is it true that the organisms that re-populate the skin after intense washing are always the same ones? (Price also measures the dynamics of skin recovery, specifically how many weeks it takes for the skin to return to its maximum bacterial carrying capacity.)

As a coda, I will note that Price mentions that “spitting on the hands may suddenly add several hundred million bacteria to the flora, but an hour later most of these organisms will have disappeared, even though the hands have not been washed in the interim.” This hypothesis actually was tested in a 2009 Science paper from the Gordon and Knight labs. (Actually they used a swab to “transplant” microbes from the tongue to the forearm, but I say that’s close enough to spitting.)

Postscript: I constantly see new research that addresses these questions!